|

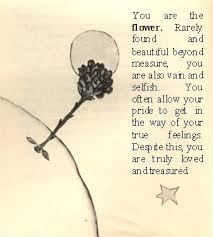

with Rich Piscopo April 14 So, our "P4C Productions Theater Troupe" reenacted episode nine of Lisa, with reassigned parts. We had great fun acting the parts! The issues we touched upon were fighting, making choices, Cause and Effect, and resigning ourselves to our "fate" (Free Will and Determinism). The class chose to talk about making choices. (I have reserved much time in the future to investigate the huge philosophical issues of Free Will and Determinism and Cause and Effect.) The facilitator put out the notion that the choices made by our ancestors brought us into existence. If our grandparents never met and did not have offspring, the self we know as "me" would not exist today. And the choices our families and we have made (relatively recently) have brought us to this moment in time and space. If it was decided that one should take ballet lessons rather than P4C during this time period, we would have never met. Every moment is filled with infinite potential. Which potential we actualize creates who we are in the future. After discussing this phenomenon, a student said, "I hate making choices." Then another added, "I think too much." The rest of the class generally agreed with these comments. So that the students did not feel strange or different, the facilitator reassured them that many of his gifted students have the same complaint. He told them that their high intelligence and active imagination allows them to see multiple consequences to any choice. This awareness can be overwhelming, thereby paralyzing them when it comes time to choose one course of action. However, the facilitator went on, the same intelligence that may cause the paralysis may save them from it. By making a "Pro and Con" list and then choosing the decisive consideration, one may choose the course of action with the most probable positive outcome. [This thinking process is discussed at length in the novella, Harry Stottlemeier's Discovery, the program that precedes Lisa. Also, as evidenced by the excellent judgment demonstrated by the students' parents, the facilitator is sure this thinking process is taught at home. However, the facilitator thought it a good time to reinforce the concept in the classroom.] The students agreed with this thinking procedure, and class ended on a positive note. April 28 It was with sadness that I announced the need for me to leave our class early this season. I informed the students that I'd be working in a summer arts program with the Developmentally Disabled. Through art, our hope is to "ignite the spark within" (our slogan) those with severe disabilities. I gave a concrete example of how I used philosophy to help me navigate a new situation. Last week, one of the clients I was introduced to was severely challenged. She had cerebral palsy and was confined to a wheel chair. Upon first appearances, she was striking to see. My first, primal, impulse was to recoil. Then I remembered what we frequently spoke about in P4C class: things are often not what they appear to be. Suspend judgment. Be open. And, true to form, once I overcame my initial fear, and got to know this severely challenged woman, I discovered that there was a wonderful, positive person inside. She had hopes and dreams, likes and dislikes, and personality. She was just like you and me, only contained in a different package. Responding to this story, a student said she often wondered how a blind person perceived the world. She wanted to "see" the world from their point of view. All the students responded similarly. Another mentioned the Seeing Eye puppy her family is raising. What a mature skill it is to be sensitive to another's point of view. We then moved on to my planned lesson about the relationship between reason, consistency, and ethical behavior. I asked, "What part does consistency play when you are forming a code by which to guide your life?" I mentioned that in chapter two of Lisa, Harry Stottlemeier said there are rules and procedures for thinking (i.e., logic). He then asked if there are rules and procedures for living. The first student said there are different sets of rules or procedures. For example, the rules and customs established by society may not apply in a survival situation. We then discussed finding a set of values for oneself. I asked if the students have yet to find theirs. All said they have found most of them. The issue of lying arose. I asked if we would betray our dignity even if we told a little lie, say to preserve someone's feelings. The first student said that there was a level that was not quite lying. I played devil's advocate and said there was either lying or telling the truth. A second stepped in and suggested we say whatever does the least harm. He went on to say that the overall value of compassion outweighs the smaller value of telling the truth under all circumstances. As our time was running out, I left the class with these questions, "Who are you? Is who you are dependent on being ethically consistent?" Thank you all for a great year! Looking forward to another great one next year. Stay curious and keep the journey of discovery alive! with Rich Piscopo March 31 We began class by comparing and contrasting the various mental acts of knowing, realizing, believing, perceiving, and comprehending. After discussing the similarities and differences of each mental act, the class agreed they are all a part of the process of understanding, but none of them alone completes the process. As one student said about learning a foreign language, "I can comprehend part of what I learn, but I don't understand all of it." Another added to this by saying about math, "I can comprehend certain steps, but not understand it in its entirety." And yet another student nicely summed up what the others were discussing by saying, "In order to understand, your knowledge needs to be complete." The first student then said, "You think you understand, but you don't." Two of the students shared the perception that there is no absolute understanding. The facilitator asked if there was a point in time when one understands everything. Someone said, "Not for humans." Then someone else said, "Understanding applies to the moment, but not for all time." Another then said, "In order to understand, you need to understand all parts." Then, referring to the earlier comment about thinking we understand but then realizing we don't, the facilitator introduced the idea of thinking we understand a person, but then realizing we don't fully understand them. One student quickly replied, "You can't fully understand a person because we're always changing, learning, growing." Another then asked, "Do you understand yourself the most?" To which another replied, "I have no idea who I am!" This honest comment led to all expressing themselves with a flood of similar comments. How refreshing to hear that one knows that they do not know! Socrates said wisdom begins with puzzlement. So begins the journey to wisdom. Let Philosophy guide the way. April 7 We began class according to my plan this week and, in order to give us all a common foundation, I read an overall summary I had written about the connection between lying and inconsistency. Then, we turned to reading the new episode of Lisa, which contains this issue. Usually, I read aloud and the class silently reads along with copies of the episode. This time, however, the group said, "Let's act it out!" We then moved on to act out the episode with assigned parts for everyone -- but, lest you think we did not accomplish anything academically, or that the students were not paying attention, after acting out the episode, these are the issues that the students brought up for discussion: conflict, confrontation, drama, romance, lying (there it is!), friendship, trust, soap operas, and peer pressure! We had time left to only begin a discussion on lying, but this is what we covered thus far: One student stated that lying is intentional and deliberate. Another drove this point home by asking if it was possible to lie accidentally. He then suggested that being inconsistent has elements of hypocrisy about it. Picking up on this, someone else stated that we don't completely tell the truth when we're inconsistent. This is an excellent beginning, and we will address these points when we reconvene next week. The evidence I take away from today's great class is this: this group is creative and innovative and can have tons of fun and laugh a lot, and yet, when the time comes, they quickly focus and become disciplined, serious thinkers. In my experience, this capability to do both is extremely rare. with Rich Piscopo March 17 During this class, we explored the sublime concept of the existence of a single, underlying, fundamental, unifying thought from which all other thoughts arise. This is a big, abstract idea, suitable for a college level class, and, understandably, the going was slow at first. By the end of class, however, we made some headway and some students were beginning to grasp it. But, we need to continue delving its depths in next week's class before we clearly and distinctly see the light of day. Here is what we covered thus far: I needed to lay some common groundwork before embarking on our intellectual expedition. After reviewing Plato's Theory of Forms, I introduced the concepts of Lao Tzu's Tao, Hinduism's Brahman, Buddhism's Dharmakaya, Ralph Waldo Emerson's Universal Being, the Unified Field Theory of physics, and the Wu Chi of Tai Chi philosophy. We then explored how each of these concepts could be considered to be one, underlying, fundamental thought. In discussing the Theory of Forms, a student astutely asked how we know we are all perceiving the same three-dimensional representation of the Form, thereby introducing the idea of relativity into our dialogue. When discussing the Unified Field Theory, I used the metaphor of an underlying, universal river flowing through the ground of Being, connecting all things. I also used the analogy of the myriad things in the universe sharing a single, common form of energy. As if everything in the universe was made of the same substance [energy], only manifest in different and unique ways [Quantum Physic's String Theory?]. For example, let's say everything was made of gold. All things would have at their core the atomic structure of gold, however, they would just be expressed in different and unique shapes. I went on to say that this energy is expressed on planet earth in trillions of different manifestations. Every insect, worm, reptile, leaf, blade of grass, bacterium, and human, all share this energy in the form of DNA. Another student shared Lao Tzu's and Fritjof Capra's perception by saying that words seemed inadequate to express what we are referring to. Capra wrote The Tao of Physics, one of our source books. She went on to say that this energy we are discussing seems to be a "surging, rushing, force of life, running through all things." I encouraged her intuitive perception, and asked her if one would be able to paint this force, since words do seem inadequate to express it. I do believe this life force was what Van Gogh was trying to capture in his painting, "Starry Night"; or what Dylan Thomas refers to in his poem, "The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower" (drives me also). Then she asked, "Does this life force age? The manifestations age, but does the force age?" This profound question led us into a discussion about the conservation of energy. Two other students reminded us that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed. She went on, "Even if this energy force existed for only one second, it would still be infinite." This statement reminded us of the Big Bang Theory, so we discussed the repercussions of it. Her inspired flash of thoughts ended by her asking, "Is life made out of the same stuff as death?" We were out of time at this point, but I did refer the class to the Zen Master Hoshin who predicted the moment he was going to die. Just before he passed he dictated the following poem, "I came from brilliancy, And return to brilliancy. What is this?" I believe this is related to the notion of the drop of water returning to the ocean. "Is life made out of the same stuff as death?" We shall continue our expedition in our next class by plumbing the depths of this weighty question. March 24 Lao Tzu Lao Tzu We returned to the surface after plumbing the depths of Being, and, fortunately, no one got the bends. We reviewed the concept of the existence of one, underlying, fundamental thought from which all other thoughts arise. This led to a dialogue about the search for the Ground of Being. As far back as the Pre-Socratics, our Western culture has been searching for a single, fundamental, unifying essence common to all things -- the Ground of Being. Does it exist? Or is everything we perceive relative to our perspective? During our dialogue about Being, the notion of Nothingness arose. I referred the class to Jean-Paul Satre's important work, Being and Nothingness. When discussing whether nothingness exists or not, a student said, "It's not nothingness, it's the unknown." It certainly is unknown. For now, we all agreed on the point that nothingness defies description. For, as soon as we describe it, it springs into existence. True nothingness, as with the similar concept of Wu Chi of Tai Chi philosophy, is beyond our dualistic mind set. Are we capable of thinking about true nothingness? As Lao Tzu says in chapter one of the Tao Te Ching, "The Tao that is spoken is not the eternal Tao." As soon as we speak it, we name and categorize it, and therefore limit it. Most likely, we will visit this concept of Being and Nothingness again in our philosophical explorations. In the meantime, I do not think it is going anywhere. It will be there waiting, in profound silence. with Rich Piscopo The Certainty of Uncertainty In keeping with our discussion on what constitutes a fact, I introduced the concept of The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. Werner Heisenberg was a physicist who said the electrons with which we use to observe the reactions of sub-atomic phenomenon affect the very phenomenon we are observing. Therefore, we cannot be certain that we are observing the phenomenon objectively, as it is in and of itself. We extrapolated that concept to our larger existence. When we observe a deer, for instance, how do we know our presence does not affect the deer's behavior? Are we observing the deer objectively, as it is in and of itself? One student said, "That kind of doubt can be applied to anything. For example, maybe this table in front of us turns into a chair when we stop seeing it." Then another offered an example, "Or, like the movie Toy Story, where all of the toys come to life after the humans leave the room." Then yet another offered a third example, "Maybe the kitchen appliances talk to each other after we leave the kitchen." This wonderful exercise in imagination led the second student to add, "I always wanted to be in the mind of a dog." I praised her for her creative curiosity, for this perspective leads one to see the world from another's point of view; to imagine what it would be like to walk in another's shoes. I went on to say that this ability to see the world from another's point of view is critical to a healthy society. We could surely use that ability in our current Congress, and in dealing with the current crisis in Ukraine. The fact that our students have this capacity to be open to another point of view gives me hope for the future. Soon enough, our students will be allowed to vote. They will have the power to effect change. With their rational perspective, I have faith they will bring about positive change; change that can defeat ignorance; change that will bring light into the world. Monday's dialogue demonstrates how philosophy is so much more than an intellectual exercise. Studying philosophy develops reasoning skills. Good reasoning skills lead to good citizenship. And, good citizenship leads to a healthy society. Therefore, studying philosophy leads to a healthy society. with Rich Piscopo February 24 - Potential and Existence During our review of the 2/17/14 class, inter-concentric connectedness was again discussed. In one student's notes from the same class, she asked that if someone is part of their parents, didn't that someone always exist [as potential]? Another responded to this by asking about people who were not yet born. She wondered if they existed [as potential]. Then yet another said, "Even when you die, you still exist because you are a part of everyone who knew you." We then called for a definition of existence. The facilitator asked if the definition of existence included becoming. One student in response to the previous comment said, "Even if a picture of you exists, you still exist after you die." At this point, in response to the call for a definition of existence, another said, "There's a difference between existence and living." He went on to say that living is a sub-category of the larger category of existence. In response to this, we heard, "So, if you live in a box, you're not existing." Playing off of this statement, another student said, "If your life is meaningless, you might as well be dead." Then a different student said, "Everyone has a purpose, even if they are unaware of it." He went on to say that our lives are inherently meaningful. One in response said, "We have unlimited potential at every moment." This comment led to a flurry of dialogue, with the group generally agreeing that we are constantly evolving. We are free at every moment to fulfill our potential. We are free at every moment to become the person we want to be! March 3 - Facts and Knowing What is a fact? I began our dialogue by giving some philosophical background to this query. I drew heavily on Bertrand Russell's book, The Problems of Philosophy, especially chapter one, "Appearance and Reality." Russell says we do not really see anything. What we really perceive are particles of light striking our retinas, and we infer what the object of our sight is. What we perceive is what Russell calls "sense-data," not the object itself. We make an association between the sense-data and the object. We do not know the object inherently, as it is in and of itself. So, if we cannot know anything inherently, how do we know what is objectively true; how do we know what a fact is? In class, I used the example of observing my green water bottle. Since, according to Russell, we can only infer that the object of our sight is a green water bottle, how can we be absolutely certain we're all observing the same green water bottle? I suggested one way to ascertain what we're seeing is to describe it to one another. We can compare our experiences and see if they correspond to the object in question -- this is the correspondence theory of truth. Although our judgment may not be absolutely certain, it would be highly probable that we are all observing the same object. But, as one student asked, how can we be certain we are talking about the same shade of green when we refer to "that green water bottle?" He said there is too much room for misinterpretation. I suggested that with so much room for misinterpretation, can we ever arrive at the objective, absolute facts connected to that water bottle? He then said we can only arrive at assumptions about the water bottle. One student responded, "Extremely probable assumptions." And another added, "Based on the past." To give our inquiry more meaning, I applied our process to the real-life circumstance of a jury involved with a murder trial weighing the evidence presented to them during the trial. I referred to the superb film, Twelve Angry Men (the 1957 monochrome version). I asked, "So, when juries arrive at a verdict, do they do so with absolute certainty?" The class unanimously said, "No. They make an assumption." Then a student said, "But assumptions are necessary." Another added, "You get as much proof as possible." I asked her, "You mean you arrive at a reasonable assumption?" Before she could answer, another asked, "Is there absolute reason, or is everything an opinion? How do we know if reason is 'reasonable'?" He then went on to describe a hierarchy of reason, with pure reason at the top and various gradations of opinion falling in order below it. A student then asked, "If there is no such thing as a fact, how can you have pure reason?" He responded by asking if reason could be broken down to numbers. She demanded he define his terms: what did he mean by "reason"? He answered, "That which has the most evidence in favor of it is reason." Another then asked, "How do we make decisions, then? If the only system we can test reason with is reason, how do we know it's valid?" I suggested we cannot, because a system cannot analyze itself with certainty. However, we can agree to its universality, and still utilize it. There was a long, reflective pause within the group. I complimented them at arriving at this intellectually honest and philosophically pure state of mind. It is a very valuable state of mind. It is one where one does not make any assumptions or jump to any conclusions. One is open. One is receptive. One's "cup is empty." After another reflective pause, a student said, "It's weird. Every thought I have is not new." Another added, "We take parts of what everyone else said before us." Then yet another said, "If everyone is using everyone else's stuff, where did it all start?" Then this was stated, "We're all part of a mosaic." To this was added, "And our mosaic is part of an even larger mosaic." Then, "Every thought is a hand-me-down." (I had been waiting to ask): "Are there any original thoughts, then?" All said no. Then one reconsidered and asked that we define "original." He said, "If original means a synthesis of what came before, then, yes, we can be original." And another student then said, "What about instincts? Could they be original?" To which another said, "Instincts are undeveloped thoughts." Before we left, I reminded everyone of an ancient quote, "There is nothing new under the sun, only new contexts." with Rich Piscopo February 10In class today, the review of our last class (1/13/14) sparked such lively dialogue that we never got to our planned lesson! During our review of social compulsion and conformity, the issue of friendship arose. What are the criteria for friendship? With the popularity of social media, has the definition of a friend changed? Can one really have 50 million "friends," as I just learned today that Justin Bieber has on Facebook? The occurrence of "playing roles" in order to comply with social conformity came up for discussion. A student said, "When I first meet someone, I have this fake persona." Then in response to her, another said, "With every friend I have, I act differently." This very self-aware and honest exchange led one student to ask, "Who are we, then?" I suggested that a person is rather like a precious gem that has many facets. We may show a different facet to each different friend, but our core values and belief system remains the same. The gem itself does not change. Our integrity remains intact. The first student then said, "A true friend is someone who accepts all of our facets." With these words, we came up with a pretty good criterion for friendship. February 17 Last week, we finally began my lesson originally planned for 2/3/14, which we never got to because of canceled classes due to weather, and regarding the class before this one (see above), the students went on a very productive tangent about friendship. The lesson plan entailed the concepts of becoming; defining a fact; separating fact from opinion; using evidence to establish facts; and understanding. We only scratched the surface of the concept of becoming, and a very nice dialogue ensued. The idea of our potential being a part of who we are in the present arose. A student remarked, "If you aspire to be something in the future, that intention defines who you are now." A second student countered that by saying, "If the thinking process is linear, then we do not become. We can only be at a certain point at a certain time." So, I offered the standard example about potential by asking if the oak tree exists within the acorn. The second student said, "No -- an acorn is an acorn and an oak tree is an oak tree." Another student countered by saying that the situation is an evolving one. She said, "The acorn and the oak tree have the same identity. The oak tree is within the acorn and the acorn is within the oak tree. The acorn is the oak tree's past." [Note: within Buddhist thinking, this concept is referred to as interconcentric connectedness. The center of everything is in the center of everything else.] Then playing off this idea, the second student replied, "Every acorn is the potential for all future oak trees." Picking up on this statement, another said, "Babies are the same way. The adult has some of the baby within her. You are your parents." Adding to that, another concluded, "You are becoming an adult before you are born." We will pick up this train of thought when we reconvene on Monday, 2/24/14. Can't wait to see where it all leads! with Sally Zeiner Reflections...For the final philosophy class of the semester, each student shared his or her own written reflection on the virtue of their choosing. We asked one another questions to clarify, and sometimes we changed our minds. This exercise encapsulated the most valuable things we have learned this semester: define your terms carefully, listen to one another, ask questions, give examples, and be willing to change your mind. The students have begun to develop these very important skills. I hope they will have the opportunity to continue to develop them in P4C in the future! Here are two of the reflection pieces submitted for publication: Courage Courage is not something that goes when you’re scared and comes back again. It's always there, you just don’t always use it. There are two kinds of courage within courage: bad courage and dumb courage. Good courage is courage itself, doing something without a really big risk, but still a risk all the same. Sometimes good courage can be doing something you’re scared to do, and overcoming a fear, and sometimes good courage doesn’t have a risk at all. Bad courage is doing a courageous thing, for an evil deed. Other than that it is just the same as good courage. Dumb courage, on the other hand, isn’t courage at all. Dumb courage is doing something that’s so dangerous, it’s stupid, like climbing Mt. Everest when you know you won’t survive. My example is that Violet is courageous when she takes charge of leading her people to a different land. She shows leadership and believes that she will someday find a new home. Anger can sometimes cause courage, but so can love. In Iron hearted Violet, most of the courage was caused by love. Violet had it, Demetrius had it, and Dragon had it, and they couldn’t have done anything without this courageous love. Love Last week we talked about all the different virtues we have: love, strength, honesty, etc. Well, I’m here to tell you there is only one, and that is love. Dragons had been treated with cruelty for millennia. One dragon was willing to throw it all away, forget all the cruelty, because Violet loved and trusted him. He repaid her with love and trust. This love and trust developed everything. This love and trust between Violet and the dragon saved humanity - the willingness to fly into the mirrored rim of the sky and sacrifice himself to save Violet. Love fits under every virtue because strength takes love, honesty takes love. That is all love. That’s what this whole story is about, isn’t it? One creature overcoming a mountain of hatred with a strong love for a small girl. Foundations of Philosophy (Ages 9-11)with Sally Zeiner To conclude last week's discussion of virtues, we tackled the difficult task of organizing our long list of ideas into specific virtues, defining them and giving examples. Our groups defined and presented the virtues of love, companionship, honesty, and courage. Each student should write a five sentence paragraph defining the virtue of their choice and offering at least one example from our reading this semester. Iron Hearted Violet is a challenging and thought provoking story, and we will spend this week discussing the philosophical issues that it raises. Students should finish the book, and come prepared to talk about one philosophical issue raised in this story. It can be something that we have already talked about - ethics, virtues, the nature of reality, and identity. Last class, students disagreed over whether the Nybbas is male or female (or neither), so all of the students should be prepared to state their opinion regarding the gender of the Nybbas, and provide examples directly from the story. “People say, 'What is the sense of our small effort?' They cannot see that we must lay one brick at a time, take one step at a time.” ― Dorothy Day Philosophy for Children (Ages 12-14)with Rich Piscopo  Plato's Allegory of the Cave Plato's Allegory of the Cave During our review last week to bring us up to speed after our winter hiatus, the class took a decidedly deep and profound direction. Because it was very philosophical in nature, I went where the children dared to go. A student asked what the difference was between experience and knowledge. This sparked a good epistemological dialogue, ending by saying knowledge (such as what one gains from books) is two-dimensional, and experience is three-dimensional. Experience falls under the category of knowledge, but is qualitatively different from book knowledge. It is deeper. I steered us back to the planned review where we explored the concept of preciousness. This brought up the phenomenon of love (love is an example of something that is precious). We spoke about the nature of love as being inexhaustible, and one cannot have too much love. The student said we may not be able to have too much love, then asked if we can have too little love. I referred to the Indian writer Yogananda who addressed this notion by saying love is out there in abundance; those who perceive there is not enough love are just not receiving it. Their "love receivers" are jammed with static. Then another student, who had been relatively quiet up to this point, said, "The truth is out there, but we just don't see it. We spend our lives seeking understanding." Then in response, another said, "Some people don't choose to seek understanding. It's easier to live behind the veil." I referred to Plato's Allegory of the Cave and to the book, Flatland. These are classic examples of the human condition of choosing "to live behind the veil". We then discussed the notion of Socratic Ignorance. We do not know the truth, yet we believe we do. When we do this, says Socrates, we are twice removed from the truth. Socrates taught that it was better to admit one's ignorance and then seek the truth; better to endure uncertainty and not jump to conclusions, than to live in an illusion. This led to a discussion on the purposes of studying philosophy. We agreed that one such purpose is to bring one to the awareness that one does indeed live behind a veil. And it is our task to try to remove it. Onward and forward. Editor's note: For those interested in learning more about Plato's Allegory of the Cave and the story, Flatland, you may enjoy a look back at this short post (with video) from Creative Thinking Circle I/Fall 2012. Foundations of Philosophy (ages 9-11) |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed